#6-1_30x40cm_gelatin silver print_2016

‘아주 먼 옛날 한 수도원에 늙은 수도승이 살고 있었단다. 그는 죽은 나무 한 그루를 산에 심었단다. 그리곤 제자에게 말했지. 나무가 다시 살아 날 때까지 매일같이 물을 주도록 해라. 제자는 매일 이른 아침 물통에 물을 담아 산에 올라가서 그 죽은 나무에 물을 주고는 저녁이 되어서야 수도원으로 돌아오곤 했지. 그렇게 3년 동안 물을 주다가 어느 날 나무에 온통 꽃이 만발 한 것을 발견 했단다.’

#4-1_30x40cm_gelatin silver print_2016

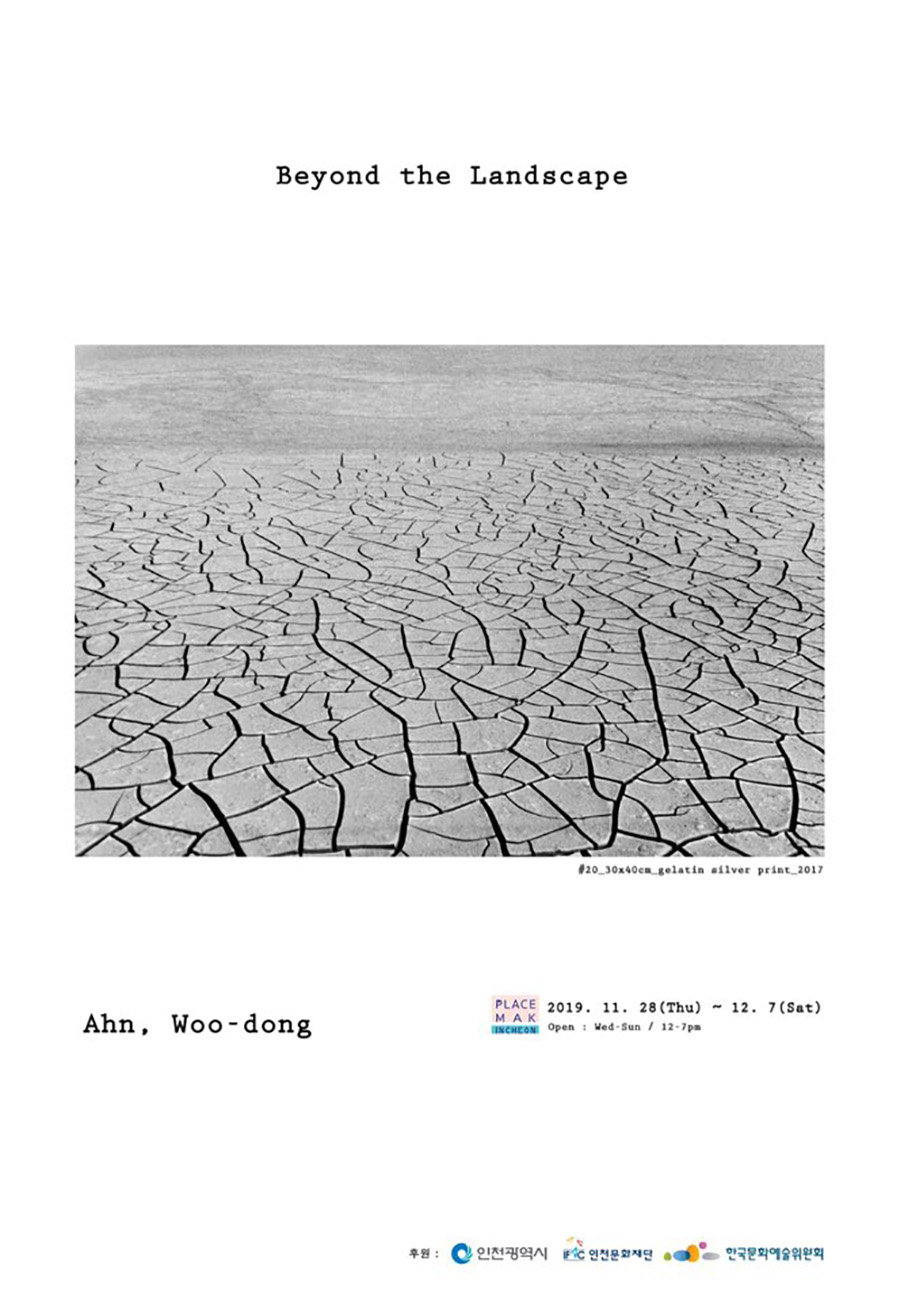

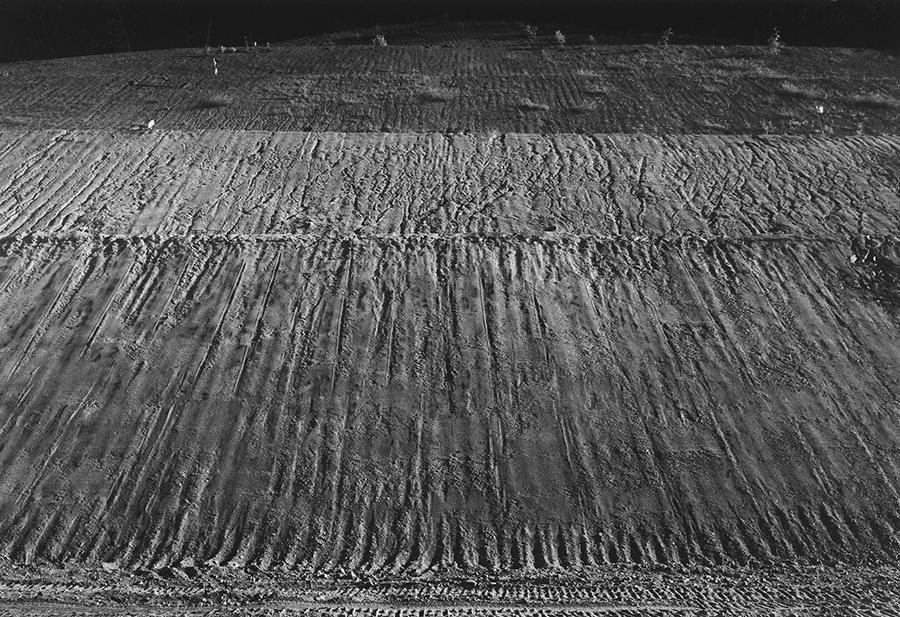

안우동 작가의 사진 속 나무는 위태롭다. 나는 저 나무를 어디선가 봤다. 러시아가 배출한 세계적인 영화감독, 안드레이 타르코프스의 1995년 영화 <희생>. 영화의 시작은 은퇴한 연극배우 안드레이와 실어증에 걸린 그의 어린 아들이 바닷가에 서 있는 앙상한 나무 한 그루에 물을 주는 장면을 롱테이크로 잡는다. 그리고 안드레이는 아들에게 늙은 수도승의 이야기를 들려준다. 수도승의 나무가 꽃을 피웠듯, 안드레이 부자가 물을 주는 나무는 꽃을 피웠을까. 다시 사진 속의 나무를 본다. 저 나무는 살아 있는 걸까, 죽은 걸까. 아니면 아직 생명은 있으되 죽어 가는 걸까. 아무리 3년 동안 물을 주며 보살핀다고 해도 죽은 나무에서 꽃을 피운다는 말을 믿어야 할까. 어린 아들에게 희망이라는 교훈을 가르쳐주려는 늙은 아버지의 동화 같은 바람이려니. 하지만 어쩌면 작가의 카메라가 향한 시선 속에 그 답이 있을지도 모른다. 안우동 작가는 그 동안 ‘한 낮의 자동차극장에 걸린 커다란 스크린의 적막함’ ‘물이 빠져버린 뒤 바닥이 드러난 겨울 야외수영장의 외로움’을 카메라에 담았다. 그 쓰임새가 다하고 난 뒤의 풍경, 혹은 변화의 과정에서 놓쳐버린 주목 받지 못한 순간들이 그의 사진 속에 기록되어 있다. 작가는 이를 변화를 기다리는 ‘중간풍경’이라 부른다. “목적과 방향을 잃어버리고 주목받지 못한 풍경이 마치 나의 존재 같다”라는 작가의 말처럼 이번 전시 역시 그런 관심의 발로다. 서해 바다 위 매립지로 만들어진 인공의 섬, 인천 송도와 영종도의 그 화려한 국제도시 탄생의 결과를 주목한 것이 아니라 그 과정과 지금의 흔적을 쫓는다. 바람에 흔들리는 앙상한 나무 한 그루, 소금기 가신 메마른 땅의 조각들, 손길이 닿지 않아 엉켜버린 덤불들. 그제야 깨닫는다. 수도승이 죽었다고 생각했던 나무, 3년 동안 물을 주며 보살폈던 나무의 깊은 곳에는 생명의 씨앗이 있었다는 것을. 그래, 누군가는 미처 인지하지 못하거나, 죽었다고 생각하는 존재들은 새로운 탄생의 변화를 맞이할 ‘기다림’의 상태라는 것을. 수전 손택은 말했다. 이런 하찮고 진부한 피사체, 스쳐지나가는 일상의 한 장면을 사진으로 마주하게 될 때 ‘사진을 통해서 바라보는 행위’는 더욱 돋보이게 된다고 말이다.

#46-2_30x40cm_gelatin silver print_2019

이런 놀라운 경험은 바다와 하늘이 닿는 수평선을 담은 사진들을 보며 더욱 확대된다. 깊이를 알 수 없는 심연의 바다와 거대한 허공처럼 보이는 하늘이 만들어낸 자연의 구도라는 장엄함 속에서 수평선위에 떠 있는 인간의 도시가 환영처럼 보인다. 아니 다시 사라진다. 환영이란 ‘눈앞에 없는 것이 있는 것처럼 보인다’고 하지 않았던가. 도시의 점들이 사라진 순간 다시 바다와 하늘의 구도만 가득하게 떠오르며 마크 로스크의 색면 추상화 연작을 마주하고 있는 듯한 감동이 밀려온다. 로스코의 시적이고 비극적인 색채가 의식을 채우고 명상으로 나아가게 하듯이 작가의 손끝에서 미세하게 조율된 빛의 명암은 사진과 회화가 보여주는 이미지를 넘어서 한 편의 시와도 같다. 그래서 니엡스도 사진을 ‘헬리오그래피’ 즉 ‘태양Helios으로 쓴 글 Graphos'이라고 했다.

#28_30x40cm_gelatin silver print_2017

안우동 작가의 사진 속에 담긴 풍경들은 죽음과 탄생 사이에 놓여 있다는 이유로 깊은 비애감을 준다. 작가는 그들에게 시선을 던지고 카메라를 향함으로써 그 연약함과 무상함에 동참한다. 작가의 시선 속에 포착된 사진들이 아니었다면 우리들은 도시의 불빛 속에 차차 눈이 멀어져갈 뿐이다. 사라져가는 과거는 숨겨진 진실만큼 중요하다고 한 수전 손택의 말을 다시 떠올려 본다. 그 ‘시간의 상처’를 작가는 지금도 쫓고 있는지 모른다.

‘대도시가 내팽겨쳤고, 잃어버렸고, 경멸했고, 짓밟은 모든 것. 그는 이 모든 것을 정리하고 수집한다. 그는 물건을 가려내고, 지혜롭게 선택한다.’ 보들레르 <와인과 하시시>를 읽으며 카메라를 든 수집가 안우동 작가를 발견한다.

최여정

Once upon a time, there was an old monk living in a monastery. He planted a dead tree in the mountains. Then he told his disciple to water the tree every day until it revived. With a bucket of water, the disciple hiked the mountain early in the morning every day, watered the tree, and did not return to the monastery until it was dark. Three years later, the disciple found the tree in full blossom.

#7-2_30x40cm_gelatin silver print_2016

The tree in Ahn Woo-dong’s work looks frail. I have seen this tree before in “The Sacrifice” (1995) by a prominent Russian director, Andrei Tarkovsky. The film opens with a scene in which a retired actor Andrei and his mute son are watering a bare tree by the sea in a long take shot. Andrei tells the story of the old monk to his son. Did the tree the father and son are watering flower just as the monk’s tree did? I look back at the tree in the photograph. Is this tree alive or dead? Or, is it going through a slow death? Is it even plausible that a dead tree can flower if one takes care of it and waters it for three years? Perhaps it is just a fairy tale about hope the aged father wants to teach his young son. Perhaps there is an answer in the artist’s Leica and where it is pointing at. For a while, Ahn Woo-dong captured ‘the desolation of a wide screen hanging over a drive-in theater in the middle of the day’ and ‘the loneliness of an empty outside pool after water is drawn in the winter’.

#34_60x40cm_gelatin silver print_2018

The landscape after the purpose it served is over or the moments that were disregarded during the time of change are captured in Ahn’s works. Ahn calls this ‘middle-landscape’, waiting for some kind of a change. Ahn notes, “The landscape that is purposeless, direction-less, thus, not gaining any attention, is just like myself,” and this is where the exhibition originates from. Ahn focuses on the trajectory of transformation and its result is the artificial islands of Songdo-island and Yeongjeongdo-island in Incheon, which are constructed upon reclaimed land from the Yellow Sea, not the creation of the pompous global city. A bare tree swinging in the wind; the barren pieces of the earth, without a trace of salt; bushes that are left without care. Now I know. Deep inside the tree that the old monk took care of for three years, the very tree the old monk thought was dead, was the seed of life. Yes, the things that people did not register or considered dead were actually in a state of ‘waiting’, ready to embrace the change of new creation. Susan Sontag stated, the “way of seeing through photography” gains more meaning when we face such a commonplace object, a moment from our daily lives.

#27_60x40cm_gelatin silver print_2017

Such a mesmerizing experience is magnified when you see the photographs of the horizon in which the sea and the sky make contact. When a city of human beings is juxtaposed against the frame in which the profound abyss of the sea and the enormous void of the sky is seen, it just looks like an apparition. No, it actually disappears. Apparition is ‘something that does not exist in your eyes that seems to take shape.’

When the dots of the city disappear, only the composition of the sea and the sky emerges in its full shape, reminding me of the sensation when I encountered Mark Rothko’s color field paintings. As Rothko’s poetic and tragic color palettes fill up one’s conscience and lead one to a state of meditation, the minutely tuned light and darkness in the hands of Ahn goes beyond the image a photograph and drawing can present, and reaches the state of poetry. That is why Niepse termed photography as heliography, a text (graphos) written by the sun (helios).

#4-2_60x40cm_gelatin silver print_2016

Ahn’s works evoke a strong feeling of grief because the landscapes are between death and creation. By looking at and photographing these landscapes, Ahn participates in their fragility and transient state. Without the photography Ahn has captured, we would gradually turn blind in the street lights of the city. Once again, I think of the words Susan Sontag said that the disappearing past is as salient as the hidden truth. Perhaps Ahn is chasing the ‘wound of time.’

‘Everything the great city abandoned, lost, despised, and trampled on. He cleans and collects these. He sorts these out, and wisely chooses.’ Reading Baudelaire’s Wine and Hashishi, I find Ahn Woo-dong, a collector with a camera.

Choi Yeo-jeong